- Home

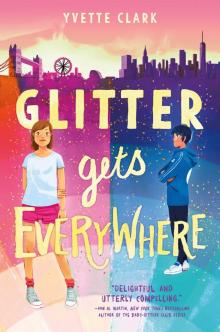

- Yvette Clark

Glitter Gets Everywhere Page 2

Glitter Gets Everywhere Read online

Page 2

Kate’s right, it is a relief that the funeral is over. Now, though, there’s a strange anticlimactic feeling, almost as if you’ve finished an exam you’ve been dreading, but as you know that you failed miserably, there is no celebration.

“I’m all right.” I sniff loudly, taking the proffered white cotton hankie, my own long since drenched with tears and snot and stuffed into Dad’s jacket pocket. “Do you know when Dad will get to the reception?”

Gran told me it is called a wake, not a reception, but that sounds weird to me—like you are waiting for the person you love to wake up. Gran said I was being silly, and it’s called that because people used to stay awake all night and sit with the body. I’m glad we didn’t have to do that.

“I think he said that they’d be about an hour. Knowing Dominic, he’ll have his hip flask with him and give your dad some on the way there. Speaking of which, I could really do with a gin and tonic.”

Dad and Dominic had gone straight from the church to take Mum to Golders Green Crematorium. Dominic’s going because he’s been Dad’s best friend since primary school and Mum knew he would need someone there with him. She didn’t want Imogen or me to go to the crematorium and asked Gran and Kate to stay with us, so it’s only Dad and Dominic who’ll be there for the last part of the funeral. I know what the crematorium looks like from the outside because we used to take the number thirteen bus past it on our way home from summer outings to Golders Hill Park. It looks like a church, although I found out that the tall tower houses the chimney rather than bells, which is a truly awful thought and something that I wish I didn’t know. Mum told us that the gardens are beautiful, with a lily pond and hundreds of crocuses. It’s where the shrink Sigmund Freud, a famous ballerina named Anna Pavlova, the author Enid Blyton, and our own grandpa were cremated, as well as hundreds of thousands of other people. Mum was always very matter-of-fact about life and death, and when she told us these things, we found them interesting rather than frightening.

I saw a cremation on television once. The coffin glided slowly down a conveyor belt to be incinerated. There were deep-purple silk curtains, which closed after the coffin slid past, while creepy organ music played, and then nothing, no more music, and no more body. After seeing the cremation on TV, I decided I would rather be buried, but Imogen told me that worms and insects eat your body, and that would be much worse. I did some research online and discovered that even with a metal-lined coffin, the creepy-crawlies can still get in, although I’m not sure how. It seems as if there are no good options. Perhaps someone will have invented one by the time I die. Imogen suggested being dropped into a pool of green acid, which she said she’d seen in a James Bond film, but that person had been alive at the time! Dad told her off for scaring me. I think Mum picked the best option available, but I’m relieved not to have to see the curtains close or to drive away from the crematorium in the shadow of that chimney.

Mum chose to have her ashes scattered on Primrose Hill, a ten-minute walk from our house and one of her favorite places. We’re going to do that next week, just Imogen, Dad, Gran, and me. From the very top, you can see all of London spread out in front of you like a picnic blanket. Before Imogen was born, Mum and Dad used to go there on dates, and when we were little, they’d take us to the top of the hill in our strollers and point out all the sights, like the London Eye and the Shard. We would sled there in the winter and fly kites there on windy autumn days. When I was about five, I rode my scooter down the hill. I was going too fast and fell off at the bottom into a pile of dog poo. Imogen laughed all the way home while I cried. Mum carried me and got dog poo on her dress, but she didn’t seem to mind. Apart from that, Primrose Hill is one of my favorite places too. There is a big piece of stone at the top of the hill with these words by a poet named William Blake engraved on it: “I have conversed with the spiritual Sun. I saw him on Primrose Hill.”

It’s where I will look for her.

Kate and I head over to Gran. She’s sitting at a corner table, deep in conversation with the vicar, who’s holding her hand between both of his. I hadn’t thought about how Gran must be feeling today. She is Mum’s mum and not just my gran. It seems stupid to only be realizing that now. How awful for her to have lost her only child. The lump in my throat that’s been there all day seems to grow. I struggle to swallow as I stand in front of her.

“Hello, Kitty, my darling,” Gran says and holds out her arms. I climb onto her lap even though I’m really too big now and slump into her. She rests her cheek gently against my head, and we sit there quietly. I suddenly feel exhausted and wish I could go to sleep.

“This room is quite lovely,” says the vicar, his booming voice interrupting the quiet. Why do people always feel the need to fill silent spaces with words? Maybe the vicar thinks it’s part of his duties to keep the conversation flowing.

We all look politely around the airy space, the gray light washing in through the windows. I would bet five pounds that the walls are painted with Farrow & Ball number 274, Ammonite, named after the color of fossils like the ones we found on holiday in Dorset last summer. Kate smiles at me and mouths the word Ammonite. She’s the one who introduced me to the wonderful world of paint colors. I give her a small nod in return, but I can’t find a smile to give back to her.

“It is lovely,” says Gran. “You would never even know you were in a pub.”

Gran thought it was inappropriate to hold the post-funeral gathering in a pub, “gastro or not,” but Dad had calmly ticked off the practicalities of the venue on his hand.

“It’s close to the church, our house is too small, and I’m pretty sure you don’t want to host it at your place, Eleanor, as some of Laura’s patients will be there. Do you really want half a dozen kids running around your living room?”

Dad was right about the children—many of Mum’s regular patients are here, along with their parents, her university friends, colleagues from the clinic, neighbors, and even a few of our teachers, who must have taken the day off school to be there. I was astonished to see Miss Barton outside the church. I always thought Mum had driven her crazy by regularly sharing her child-psychology wisdom during parents’ evenings, but apparently not, since my teary-eyed English teacher hugged me and told me how wonderful she thought Mum was.

“I quite agree, Eleanor,” replies the vicar. “I may recommend this location to other families. It strikes me that this room would work equally well for a christening party or even a small wedding reception, and the food is absolutely delicious!”

The vicar’s plate is piled precariously high with a tower of mini Yorkshire puddings, Scotch eggs, small sausage rolls, and little triangles of Welsh rarebit, all of which were Mum’s favorite comfort foods.

“Do you know, when Laura was a child, she thought that Welsh rarebit was made from Welsh rabbits? I had to explain to her that it was just a name for posh cheese on toast, but she didn’t believe me for years. She flat-out refused to eat it until she was about seven, and cried when anyone else did. Her favorite book was Peter Rabbit at the time.” Gran smiles at the memory. “Would you like anything to eat, Kitty, dear?”

“No, thank you. I’m not hungry,” I say.

The vicar looks embarrassed by his healthy appetite, and edges his overflowing plate to the side of the table.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake!” Gran says. “Can you believe it? Sorry, Vicar, but Mrs. Allison has brought that damned dog with her.”

We all turn to the door and see our neighbor bustling in with Sir Lancelot, her asthmatic French bulldog, in her arms. Sir Lancelot is a glum-looking creature, constantly snuffling and with numerous digestive issues resulting in horrible farts, which Dad says cause flowers to wilt. In our three years of living next door to Mrs. Allison, she had always been very friendly, but we never got to know her well, busy as we were with life. However, when the shadow of death appeared, so did Mrs. Allison, and over the next six months, she’d become a regular visitor to our house. She popped around almost daily w

ith casseroles, banana bread, and apple tarts, the ubiquitous Sir Lancelot panting placidly at her heels. Dad and Gran found her visits annoying, and I even overheard Gran describe Mrs. Allison as an ambulance chaser, but Mum was very fond of her, and everyone enjoyed her cooking. I think Mum felt that in Mrs. Allison, she had recruited another valuable member for “Team Wentworth”—one who would ensure that we ate well when Mum was no longer in the kitchen. Gran eats like a bird—a slice of bread, some hard cheese, and an apple are her go-to supper. Dad is a big fan of takeout curries and frozen pizza. Mrs. Allison, however, is a talented and prolific baker of pies, stews, tarts, and pastries.

“Hello, all!” says Mrs. Allison, her indigo hat quivering along with her bottom lip. She sets Sir Lancelot down on the floor next to the vicar with relief. I know from experience that dog is heavy.

“Beautiful service, wasn’t it? Just lovely. And the choir—well, music always gets me right here.” Mrs. Allison presses her ample bosom mournfully. “Stop it, Sir Lancelot! I’m so sorry, Vicar. I think he’s after your Yorkshire pudding.”

Sir Lancelot is wheezing even more than usual, his eyes bulging out of his small, round head. Even Gran looks concerned.

“Poor baby, are you hungry? Did mummy not give you enough breakfast?” Mrs. Allison asks the dog, reaching down to pat him. In response, Sir Lancelot makes a surprisingly agile leap toward the vicar’s plate and manages to grab a sausage roll before spilling the rest of the food onto the vicar’s lap.

“Oh my!” yelps the vicar, jumping to his feet, which gives Sir Lancelot the opportunity to snaffle a Scotch egg.

“Get down, Sir Lancelot, you naughty boy! I can’t take you anywhere.”

Mrs. Allison kneels to pick up the food that’s on the floor and attempts unsuccessfully to pry the Scotch egg from Sir Lancelot’s determined jaws. Gran looks on in horror at the vicar, who is trying in vain to wipe the gloopy melted cheese of the Welsh rarebit from his black trousers.

I catch Kate’s eye and smile for what feels like the first time in weeks.

“I really hope that your mum saw that,” Kate whispers in my ear. “She would have absolutely loved the look on your gran’s face.”

Chapter Four

Back to School

We are going back to school today, which everyone agrees is by far the best place for us to be. Imogen has been flitting about the house ever since the funeral. She walks into rooms, then spins around and leaves. She switches television channels manically and opens and closes books without reading a single word. She looks in the fridge and shuts it again without taking anything out. The energy radiates off her, in stark contrast to my lethargy. I drag myself between my bedroom, the bathroom, and the kitchen. I avoid the living room, which is flooded with light and air, since Gran has taken to leaving the doors open to let the outside in. I find the garden offensive. It’s bustling with life as flowers burst into color, and birds hop around the lawn, watched by my cat, Cleo, who skulks in the bushes. All I want to do is sleep, but Dad or Gran, one of whom comes into my room every day before I’m even awake, coaxes me out of bed each morning before eight. Sleeping is the only escape. The horrible part is waking up, because, for a few moments, I struggle to figure out what is wrong before the realization washes over me, taking my breath away. One morning I forgot that Mum was dead for about twenty seconds, and then it hit me. I was crushed under a ton of rocks of sadness. These days one or all of us emerge from our separate bedrooms in the morning looking as if we’ve just crawled out of a collapsed building, invisible dust covering us and pain pressing on our chests.

I don’t dream, I never have, well, not that I can remember. Imogen does though, and sometimes I hear her crying out in her sleep. I go to her room and often, Dad is already there, stroking her hair. If he’s not, I sit down and do it until she settles. I like doing that for her. A few years ago in our old house, where Imogen and I shared a room, she woke up in the night screaming that praying mantises were climbing up her bed. I had no idea what a praying mantis was, but it sounded terrifying, so I raced to Mum and Dad’s room, my shrieks even louder than my sister’s. My parents were both already out of bed and running down the landing toward our room. Mum scooped me up in her arms while Dad charged into the bedroom to face Imogen’s demons. Later, when Imogen and I had been calmed down with cuddles and cups of warm milk and were tucked back into our mantis-free beds, I told my sister that she should keep garlic under her pillow from now on.

“What for?” she asked suspiciously.

“The praying mantis, of course. They don’t like garlic or daylight.”

“Kitty, you idiot. They’re a type of insect, not vampires!”

I could tell by her voice that she was smiling, and that made me feel happy. The next day I stole two cloves of garlic from the kitchen and tucked one under each of our mattresses, and guess what—no more praying mantises.

It feels strange to walk through the familiar school gates. Mrs. Brooks, our scarily efficient headmistress, is standing by the front door as she does every day, shaking hands with each girl, ensuring they make eye contact while they do so and giving them a top-to-toe sweep of her steely eyes as she checks for uniform violations. In my first year at the school, Mrs. Brooks had told Mum that the glossy, black patent leather shoes I was proudly sporting were more suitable for parties than for the classroom. Mum returned her steady gaze, and politely explained that these were the shoes I would be wearing until my feet grew out of them, but that she would be sure to buy plain leather next time.

As Imogen and I file through the door, the headmistress embraces us. She looks bony and angular but is surprisingly soft to touch.

“Welcome back, girls. I want you to know that the whole community at Haverstock Girls’ School is here to support you during this difficult time. You may come and see me whenever you feel the need to talk. I have a kettle in my office and a rather large supply of excellent chocolate chip cookies.” She smiles, and her eyes crinkle in a friendly way. “Even if you would simply like to sit quietly, read a book, and have a cookie, you will be very welcome.”

Mrs. Brooks considers Imogen’s eyeliner and non-uniform-compliant black tights—they should be navy—but apparently decides to give her a pass on her first day back since she gently herds us through the glossy red doors.

“Are you going to go and have a chocolate chip cookie with Mrs. Brooks, Imo?” I ask.

“God, no! She won’t let you just sit there and read, you know. You’ll have to talk to her about your feelings.”

Imogen disappears into a gaggle of navy-blue girls, and I watch her go, feeling lost. I’d like to have a cookie and a cup of tea in Mrs. Brooks’s office. It’s always lovely and quiet up there, just the friendly ticktocking of the grandmother clock.

“Well, it is a girls’ school after all, Kitty, dear,” Mrs. Brooks said when I told her that I liked the grandfather clock.

Jessica greets me with a hug and proceeds to stay doggedly by my side for the rest of the day, her arm looped protectively through mine. She only unhooks her arm during lessons, while we eat lunch, and when one of us goes to the loo. Jess doesn’t ask about the funeral but just says that her mum said it was “beautiful” and then pauses to see if I want to say anything. When I don’t reply, she starts to tell me about a family of foxes that has recently taken up residence underneath her garden shed. Jess loves all animals and wants to be a vet or a wildlife television presenter when she grows up—probably both if she has time. She’s been trying to lure the foxes out from under the shed with various types of food stolen from her kitchen.

“I left a sandwich out for them this morning,” she says. “They didn’t eat the apple slices I left them yesterday, so I cut up a cheddar cheese sandwich into fox-bite-size pieces. It was whole-wheat bread, because my mum won’t buy the white stuff. I hope the foxes don’t mind. I prefer white bread. Foxes probably do too.”

“You could try cat treats,” I say, grateful that the conversation has moved on.

“I could bring in some of Cleo’s tomorrow if the foxes don’t like the sandwiches. Or I could ask Mrs. Allison for some of Sir Lancelot’s treats.”

“Brilliant idea! Why didn’t I think of that? I’ll call you when I get home to let you know if they ate the sandwiches.”

“How will you know that it was the foxes that ate them and not a bird or something?”

“Birds don’t eat cheese sandwiches, Kitty,” Jess says confidently, so we leave it at that.

Even though there is more to distract me at school than at home, Mum is still everywhere. I know she’d enjoy the book we have just started in English, The Secret Garden. I bet she read it when she was younger; I’ll ask Gran. Mum could have helped me with my French homework of writing a conversation in a café. “Je voudrais un croissant” is as far as I’ve got. Who is going to help me with French and English now? My parents divided any homework help that Imogen or I might need between the two of them. Mum always said that she did the words and Dad did the numbers in their relationship.

In art, we’re finishing our drawings of the sarcophagus that we sketched when we went on a school trip to the British Museum two weeks ago. Mrs. Kerr, the art teacher, looks mortified when she catches my eye after telling the class to continue to work on their mummies. I give her a sympathetic smile to let her know not to feel awkward about it, and to show her that I’m fine, I walk across the classroom to sharpen my pencils. A memory smacks me right between the eyes of Mum and her automatic pencil sharpener. Dad laughed at her for buying it, but she loved it. I used to sit next to her at the kitchen table handing her one pencil after another, which she stuck into the machine and pushed down, causing it to whirr until a little click indicated that the pencil was ready. Mum would remove it and study its perfect point with satisfaction. My job was to empty the curly shavings when the sharpener was full. Mum said they would have made excellent bedding for a hamster if we had one. Dad muttered something about lead poisoning, and then I delivered ten perfectly sharpened pencils to Imogen. All of this comes back to me as I stand frozen in the classroom, my unsharpened pencil in hand. It’s like I’m in an episode of Doctor Who and entered the Tardis only to emerge five years earlier in my kitchen with Mum’s warm arm resting against mine.

Glitter Gets Everywhere

Glitter Gets Everywhere