- Home

- Yvette Clark

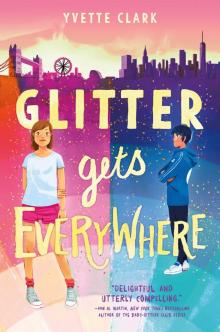

Glitter Gets Everywhere

Glitter Gets Everywhere Read online

Dedication

* * *

For Abel, Beatrice, and Gabriel, who give me love and laughter every single day

* * *

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One: Waiting at the Window

Chapter Two: At the Church

Chapter Three: Light Relief

Chapter Four: Back to School

Chapter Five: Ponytail Girl to the Rescue

Chapter Six: Eavesdropping

Chapter Seven: Kneading Therapy

Chapter Eight: The Great British Baker

Chapter Nine: Baking Bites Back

Chapter Ten: The Big Apple

Chapter Eleven: Dayroom Yellow

Chapter Twelve: Cake for Breakfast

Chapter Thirteen: Excess Baggage

Chapter Fourteen: Lady Liberty Green

Chapter Fifteen: Lost in Translation

Chapter Sixteen: The Boy With the Blue Hair

Chapter Seventeen: Chutes and Ladders

Chapter Eighteen: Gluten-Free Granola

Chapter Nineteen: Trick or Treat

Chapter Twenty: Color Therapy

Chapter Twenty-One: Turkey Day

Chapter Twenty-Two: Ponytail Girl Strikes Back

Chapter Twenty-Three: Imogen’s Ice Cream

Chapter Twenty-Four: Glitter Everywhere

Chapter Twenty-Five: A Very White Christmas

Chapter Twenty-Six: January Blues

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Sharing Is Caring

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Be My Valentine

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Unhappy Anniversary

Chapter Thirty: Accident and Emergency

Chapter Thirty-One: Home Is Where the Heart Is

Chapter Thirty-Two: Twelve Today

Chapter Thirty-Three: Waiting at the Same Window

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Waiting at the Window

I can’t decide if today is the second or third worst day of my life. Perhaps half past ten in the morning is too early to tell. It is the most terrible Friday and the saddest rainy day ever. The absolute worst day of my life was an inappropriately sunny Tuesday earlier this week. I know that for sure. The other contender for second place was the day a few months ago when I fully understood the unbearable truth of what was going to happen.

The London street below my window is wet, gray, and deserted on this March morning. I check the Farrow & Ball color chart taped to my wall. There are hundreds of different colors of paint, and fifty-five of them are shades of white and cream. My eyes search for the perfect match until they land on color number 272, Plummett. How perfect, as I have plummeted here to land at my window seat, the fall so fast that my stomach is in my throat, and my ears hurt.

The cherry trees on our street are finally blooming, their flowers arriving just in time to say hello and goodbye to Mum. Their pale-pink blossoms, color number 245, Middleton Pink, are lapping up the rain.

If it weren’t raining, I’d like to go to the park with my best friend, Jessica, but she’ll be at school today along with everyone else. I wish that I were there, sitting at my desk next to her while we try to conjugate French verbs under the watchful eye of Madame Olivier. Jessica’s mum is coming today, but she said that Jess is “far too young, Kitty, dear,” even though she’s the same age as me. When Jessica left yesterday, she squeezed my hand so tightly that her nails left little crescent-moon-shaped indents in my skin, which were still there when I went to bed.

Mum always smiled on rainy days like this one, closing her eyes and tilting her face to the heavens. She hardly ever used an umbrella, preferring instead to wear a sky-blue raincoat with a hood that was forever blowing down. Mum said that the rain is like a beauty treatment from nature, so why would you want to cover your face? Dad would mutter that it was nice weather for ducks, and grab his enormous black umbrella, determination to stay dry between home, train station, and office written on his face.

Dad hasn’t been to work for nearly two weeks now.

I don’t usually like the rain, but today this endless London drizzle suits me just fine. My sister, Imogen, said that when the weather reflects a character’s mood in a book or poem, it’s called pathetic fallacy, or something like that. She’s thirteen and knows everything, or thinks she does. I’m ten and know that I don’t. According to Imogen when I’m her age, I still won’t know the things she does because she got the looks and the brains in the family. When I asked Mum what I got, she smiled at me.

“Kitty, you have your own looks and brains, no better or worse than your sister’s, but just perfect for you.”

Well, that was definitely a lie, because it’s a fact that Imogen is prettier than me, and everyone knows it. I have a bump on my nose, and people often ask me how I broke it. I didn’t! Imogen’s nose is perfect. Dad said that “physical perfection can lack character,” but he was just saying that a) to make me feel better, and b) because his nose is identical to mine.

Imogen has long silky honey-colored hair, and bright-blue eyes just like Mum’s. Her hair hangs to the middle of her back, covering her bra strap. The fact that she wears a bra and that her locks reach it are two more ticks in the Imogen column. She looks as if she belongs in California with sun, surfers, and palm trees, rather than in this leafy part of North London. Imogen is the beauty of the family, and I, while not quite the beast, am definitely the plain Jane. I have dull brown hair cut neatly into a blunt chin-length bob, which the paint chart pronounces an exact match for color number forty, Mouse’s Back. My eyes are the same rodent color as my hair. I can run faster than my sister though, and I’m going to be taller. I’m catching up already.

I press my burning cheek against the cool window and study the street below, but there’s nothing to see; only the cars parked outside their houses tell of the existence of my neighbors. Instead, I look down at the itchy navy-blue pleated skirt I’m wearing, purchased on a miserable shopping trip the day before. I wanted a black top to wear with the skirt, but Gran said no.

“Black is not a color for children, Kitty. Anyway, navy and black would make you look like a bruise.”

“I feel like a bruise,” I replied, which made Gran’s face soften slowly, eventually crumpling in on itself like a paper bag. She turned away, and I quickly shoved the black sweater back on the shelf and picked up the navy one. I trailed after Gran through the store until we arrived at the cash register, where she paid in silence.

“Kitty, love, the car’s going to be here soon,” Dad calls up the stairs. “Are you ready to go?”

Of course I’m not ready. How could I ever be ready for this? I touch the silver heart on the charm bracelet Mum gave to me a few weeks ago. The solitary charm looks almost as lonely as I feel. Imogen had been given the same bracelet and charm. We aren’t sure where or when Mum had bought them. I suppose she must have ordered them online. We don’t know if she gave anything to Dad, and we won’t ever ask him. There’s so much we don’t know. Mum also left a pile of letters in thick cream envelopes for Imogen and me to read on our next three birthdays. The envelopes are decorated with drawings of flowers, love hearts, and sunshines, with our name and age written in the middle in Mum’s curly handwriting. Three letters just aren’t enough. I’ll only be thirteen when I get the last one. Why did Mum think it was okay to stop the letters then? What about when I’m eighteen, or twenty-five, thirty-seven, fifty-two, or even seventy? Some people still get letters from their mums at that age. When Dad showed us the six envelopes, I asked him why there were only three each. He put his head in his hands an

d spoke so quietly that I could barely make out the words.

“She had to stop writing, love. There was no more time.”

Maybe he hadn’t spoken at all but just sighed out one single, sad breath. He didn’t notice when I crept out of the kitchen and upstairs to my room. Lying awake in bed that night I realized that Imogen had three extra years with Mum. This thought ticked back and forth in my brain like a metronome and gave me a headache. It took me ages to get to sleep.

Through the window, I see a large, glossy black car turning onto the street. It looks as if it might not fit, and it crosses my mind how awkward it would be if it scraped one of the neighbors’ cars, setting off their alarm in a shrill wailing. It’s a very posh car, much fancier than our old Volvo, which is parked forlornly outside. Mum had planned to get an environmentally friendlier car called a Prius, but that doesn’t matter anymore. Nobody’s going to care now about the carbon emissions of our old Volvo. This black shiny monster gliding toward my house is definitely not good for the environment and Mum would hate it. I hope she isn’t in a car like this one. She’s probably already at the church, waiting silently for us to arrive.

Saint Stephen’s Church is where Mum and Dad got married and where Imogen and I were christened. Imogen was a pink, frilly flower girl at their wedding. She apparently took ages to walk down the aisle, because she was trying to do pointy ballet toes while she scattered clouds of rose petals. Mum was five months pregnant with me on their wedding day, so I actually walked down the aisle with her, tucked neatly under her billowing ivory dress. I’ve always wanted to be a real bridesmaid, but I don’t care anymore. I wouldn’t do it now even if someone asked me, and they probably will because everyone feels sorry for me.

It’s time to go.

Chapter Two

At the Church

Hampstead High Street is bustling with locals and tourists who crowd the narrow sidewalks despite the rain. People must think we are in a wedding car, as several shoppers smile and wave at us enthusiastically during our slow drive up the treelined hill, eliciting tut-tutting and vigorous eye-rolling from Gran. They peer into the car as we wait at the traffic lights, their grins disappearing as they take in the black-clad, red-eyed occupants. People turn away wishing they had never seen us.

It isn’t even that far to the church from our house. We should have walked. Mum would have preferred that. She liked to walk everywhere, dragging us in her wake. It’s one and a half miles from our house to Gran’s, and providing the weather was fine, and we had the time, we always walked there and back. Fine weather for Mum was anything that didn’t involve torrential rain, thunder, or lightning.

When we arrive at the ancient church, the car glides into a miraculously empty parking space, directly in front of the gate. I wonder if someone put traffic cones out there so we’d have a place to park when we arrived, and then discreetly whisked them away as we turned the corner. The vicar is waiting under his huge umbrella to greet us. He smiles kindly at Imogen and me and shakes hands and speaks softly with Dad and Gran.

It’s so quiet inside the church that our footsteps echo embarrassingly as we walk to the front pew to take our seats. It’s gloomy too, as the church is lit only by dozens of flickering candles and the gray light that is seeping in through the stained-glass windows. When I twist around in my seat, I see the church is full. Although I recognize lots of faces, there are just as many people I don’t know. Who are they all, and how did they know my mum? Whenever I catch someone’s eye they give me a small, sad smile and hold my gaze, as if to turn away from a child’s sadness would be shameful, but I wouldn’t blame them at all if they did.

Somebody must have given me the order of service as I entered the church because I’m clutching it in my hands. According to the card, the song the choir is currently singing is called “Make Me a Channel of Your Peace.” We’d worked together on the program for the funeral, or memorial, as we were supposed to be calling it—the least fun family activity imaginable. Imogen and I were allowed to choose the picture of Mum for the front cover, and for once we were in total agreement, not a single argument; there was just one photo we both wanted. The photograph had been taken in my godmother Kate’s garden before cancer became part of my family. It was already there though, hiding malevolently behind Mum’s radiant smile, an unwelcome and uninvited guest. In the photo, Mum is gazing squarely at the camera half laughing, her nose crinkled up and her grass-green dress blowing around her legs. She is so healthy and full of life in the picture, so very different from the way she looked over the last few months. I turn the card over in my lap because it makes my heart hurt even more to see her longed-for face. The back of the order of service is mercifully blank. Just like my mum, I realize, here and then not, everything and then nothing. How can that be? I start to think about what I wouldn’t give to have her back with me, but stop because it’s scary.

Imogen and I are wedged tightly in between Dad and Gran, even though they have space on either side of them. Nobody else has chosen to sit with us in this pew. Attending a funeral is the opposite of going to a concert or the theater. At a funeral, nobody wants to sit at the front. It’s better to be at the back—the farther away you are, the less it hurts. Imogen is staring furiously into her lap, her fingers folding and unfolding the fabric of her dress. How come she was allowed to wear black? Dad and Gran are alternating between looking at us and looking at the coffin, which is already in position at the front of the church, just as Mum had wanted. My sister and I did a lot of listening at doors over the past few months. As Mum got more and more ill, our ears were pressed closer and closer to doors and walls. Our parents tried to include us in the funeral planning. In Mum’s professional opinion, she probably thought it was healthy to involve us. This particular detail, however, I had eavesdropped a few weeks ago.

“Rob, there is absolutely no way I want you and a bunch of our friends carrying me down the same aisle I walked down to marry you. It’s incredibly morbid. I think it’s more appropriate if I’m there when everyone arrives.”

“Appropriate? Maybe if we imagine that you’ll be hosting the world’s most tragic cocktail party, then yes, it’s appropriate,” said Dad.

“Rob, I agree with Laura,” said Gran. “It is in fact quite dignified to be there, waiting for the mourners to arrive. I wonder why more people don’t do it that way. I always worry one of the pallbearers is going to trip and drop the coffin, and probably in this case it would be your idiotic friend Dominic. He always was a clumsy oaf. Do you remember how he spilled red wine all over me at your wedding? I never did get the stain out of that lovely trouser suit.”

As she so often did, Gran settled the matter. Or maybe Dad thought there was a reasonable chance that Dominic might drop the coffin. Either way, there was no further discussion, and so there Mum lay when we arrived, gently waiting. I hate to think of her in that box. Her actual body is lying there at the front of the church, and she is entirely on her own. I start to shake, Dad pulls me closer into him, and the service begins.

Most of the next forty-five minutes are a blur. Everything that the vicar says gets lost in the space between his mouth and my ears. I miss Kate’s reading entirely, but when Dad walks up to the front of the church, I sit up, stick straight, and hold my breath. He stands there for a long moment leaning against the lectern, his face tired and pale, and his hair too long. His suit, shirt, and tie are pristine, in stark contrast to the body inhabiting them. When he speaks, his voice is surprisingly loud, clear, and comforting, as if he is there to make the rest of us feel a bit better.

“Laura asked me to read this poem to you today. As you know, she loved poetry, and when she found this piece she knew right away it was what she wanted to share with all of you:

“I give you this one thought to keep.

I am with you still. I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow.

I am the diamond glints on the snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain.

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awake in the morning’s hush,

I am the swift, uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night

Do not think of me as gone.

I am with you still in each new dawn.”

I mouth the words along with Dad. The poem is printed out in the order of service, but I don’t need to look at the words. I know every line by heart. I asked Mum to read it to me over and over again after she’d chosen it so that I could hear her voice in my head at this exact moment. My sister must have taken my hand, or maybe I reached for hers, since our fingers are entwined. I know that Imogen, like me, can hear Mum’s voice speaking the words along with Dad. I think about the woman who wrote the poem and who she might have written it for, all those years ago. I bet she was a mother too. I can imagine her sitting beside a stream, beneath a weeping willow tree, conjuring these words to comfort the family she had to leave behind. Mum said we only needed to remember five of the words and that they’ll always be true—“I am with you still.” I can’t feel her, though.

Chapter Three

Light Relief

“Thank goodness that’s over!” exclaims Kate, enveloping me and my tear-soaked face in caramel-colored cashmere and a cloud of perfume that tickles the back of my throat. Kate’s usually immaculate makeup is smeared, with small pale tear trails down her cheeks and dark smudges under her eyes. I suppose nobody is looking their best today, despite having dressed carefully for the occasion. Gran sent Imogen to the loo with her friend Lily to try to remove her black eyeliner, which has left inky-looking streaks on her face.

“Let me look at my beautiful goddaughter,” Kate says, leaning back to examine my pink blotchy cheeks. She tucks a stray strand of hair behind one ear. “Yes, just as gorgeous as ever, and so brave. How are you feeling, my darling?”

Glitter Gets Everywhere

Glitter Gets Everywhere